Aristotelia, the setting of celestial spheres

This setting is based on Blood & Treasure, Dark Dungeons, and Voidspanners.In Aristotelia, the physics of space travel are very different from reality. The night sky is actually the surface of a massive "celestial sphere" that encompasses the solar system. Outside of the sphere is the "luminiferous aether" and access to other celestial spheres in the universe.

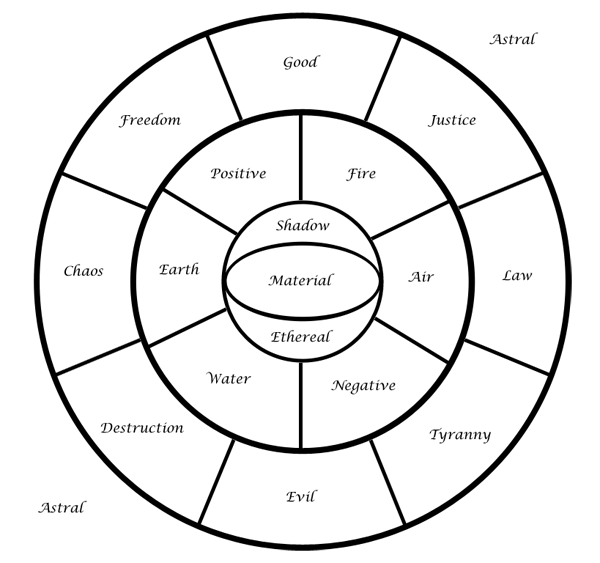

Celestial spheres are not all made the same, but may have different local physics. One sphere might be heliocentric while another is geocentric. One sphere might be filled with an airless "void" (astronauts carry their own air supply without needing suits), while another is full of a breathable "ether." One sphere might have its inner and outer planes as inner and outer planets inside the sphere, while another has its inner planes inside the sphere and its outer planes outside the sphere.

Propulsion systems include:

- Sails of Skysailing are a magical effect that allow ships to fly through the air, void, and luminiferous aether. These are made from the silk of phase spiders and may be attached to conventional sailing ships.

- Void engines are magical items that propel vessels through the void. These need to be activated by a power source, such as a wand, a wizard, or a sacrificial victim.

- Ether sails are magical sails that ride the ether winds. These do not need a power source, but they are only effective in ether currents.

- Tree ships are rare vessels created by elfin druids.

Alhazenia, the setting of outer space

This setting is based on all those settings in which astronomy and outer space operates as it does in real life.In Alhazenia, star systems and outer space functions as it does in reality. This makes it easy for a player familiar with modern astronomy to enter the setting. There are multiple competing methods for space travel, not one universal method used across the universe. These include fantasy magic, science fiction technology, and more based on a variety of different power sources.

Power sources harnessed for applications as propulsion systems include:

- Magic. Wizards can cast spells or create magic items that allow space travel.

- FTL drive. Seen in Dragonstar, Starfinder, and many other settings. These are taken straight out of scifi, so read scifi for details. I dislike this approach as I find it lazy and bland.

- Flux culler. Seen in Aether & Flux: Sailing the Traverse. These non-magical devices generate the electrical force known as "flux," which provides propulsion by interacting repulsively with the "aether" suffusing the universe.

- Aetherdrive. Seen in Aethera Campaign Setting. These are "magic-technology hybrids" powered by "highly toxic crystals" with "naturally telekinetic properties."

Fitting the planes of existence into Alhazenia requires more work. I should save that for a future post.